Masters of War

A Closer Look at "Falling Man"

👋 This is another in a series of monthly posts investigating books that have influenced my writing. In case you missed them, you can read some of the previous ones here:

This past Saturday, on the sunniest day of the summer, a group of writers gathered in the dank snug of a Dublin pub to hear each other read from unpublished work. I decided to read from a novel-in-progress because I’d never read from it aloud. The book follows a pair of brothers who grow up outside of Boston in the mid-2000s. One of the brothers, Donald, has a boyish fixation on military aircraft. In the monomaniacal way that eleven-year-old boys tend to love things, he loves their circumstance, their attributes. And there is one airplane he loves most of all.

If Donald could see any airplane in person, it would be the Northrop B-2 Spirit heavy strategic bomber. It is his favourite airplane. It is his favourite airplane by a mile. He does not have a second favourite airplane. There is no point in having a second favourite airplane when your favourite airplane is the best one of them all, the Northrop B-2 Spirit American heavy strategic bomber. No other country in the world has as advanced an air force as the United States Air Force, and no plane in the United States Air Force fleet is as advanced a heavy strategic bomber as the Northrop B-2 Spirit. It keeps Donald, and everyone he knows and loves, safe.

None of us knew it, but at the exact time I read this passage, B-2s were being deployed from Whiteman Air Force Base on their first major bombing run since 2017. Some flew west, a Pacific diversion. Another seven flew east, over the Atlantic, and by midnight Dublin time, they had dropped fourteen 30,000-pound bunker-busting missiles on three nuclear targets in Iran.

Now is the point at which you might be asking yourself, having read the title and subtitle of this post: when is this guy going to get to Don DeLillo?

Falling Man, published in 2007, concerns Keith Neudecker on the day of the September 11th terrorist attacks. We meet Keith walking out of one of towers, bloody and covered in grey soot, a briefcase in hand that does not, he discovers at home, actually belong to him. It is a daring book that tries to make sense of something incomprehensible by inhabiting the center of its experience. By looking from the inside out.

Falling Man follows Keith in the days immediately following the attacks, starting with his arrival to the apartment of his estranged wife. They try to make sense of each other, of themselves, while in the background, America does the same. True to DeLillo’s work, this is not a novel informed by narrative but by overlapping symbols, less interested in answering the questions they pose than examining their context.

Take, for example, the eponymous Falling Man, a guerilla artist who dangles from the sides of buildings dressed in a suit, posing to recreate those who jumped to their deaths from the World Trade Center.

Or perhaps Keith’s long-standing weekly poker game, which gradually escalated into a rigid affair of harshly abided rules: no food; no drinking; no smoking; no chatter. The friends came to love the ritual more than what was being ritualised until, one night, the structure ruptures under its own weight and they lift all the rules all at once. In the present, the game is cancelled. Half of the players were killed in the attacks.

Or his estranged wife Lianne’s writing therapy group, whose members begin to succumb to their Alzheimer’s and slowly lose their ability to write. This thread relates to how Lianne, worried about developing the dementia that is killing her mother, begins performing brain teaser exercises. When she finally builds the courage to see a doctor, she is told that she is fine, but continues to find comfort in the brain teasers anyway.

Any one of these symbols could power a novel. They each provide a system and subvert it, leaving the reader to ponder, say, the efficacy of making art from trauma, especially national trauma. Or the sliding scale of autocracy. Or the comfort of ritualization. Or, in a fascinating exchange Keith has with a fellow survivor, how one can reconcile tragedy with faith in a higher power, especially tragedy caused by those who were, in their own horrible way, ultimately devoted to a higher power of their own.

Taken together, these overlapping symbols are debilitatingly DeLillian, this patchwork composite that says something about our ability—or inability—to cope as the world comes apart at its seams.

Falling Man concerns characters who take control amidst uncontrollable environments, no matter how minutely. A mother dies of dementia and her daughter tries to work out her brain. A husband survives a terrorist attack and begins an extramarital affair. An artist lives through national rupture and embodies the most traumatic icon of its suffering.

Notably, all of these actions becomes rituals of comfort where the ritualization itself becomes the comfort. The poker ostensibly at the heart of a convoluted home game becomes secondary in focus to the militant adherence to the home game rules themselves. There is no medical need for Lianne to perform brain teasers, but they provide her reassurance.

These are not cures, DeLillo seems to say. They are salves. Like the child who watches September 11th on a television screen and grows up to revere the military because militarism is an answer to a question of fear. Like the author who invents that child, trying to construct a system of coherence for a world that defies all rational understanding.

Because what does it mean to write about the sublimation of mediated militarism, the fetishization of national defence, and to go on to read that work aloud while, simultaneously, 420,000 pounds of explosives are dropped by the same plane you read about? While the President of the United States declares, for the second time in your life, a war in the Middle East? It becomes impossible to distinguish the aestheticization of politics from their interrogation.

An airplane is flown into a skyscraper. Does writing from the perspective of someone walking out of the stricken tower help to understand why it was struck? Or from the perspective of the man who hijacked the plane? I do not know whether these actions are palliative or escapist, acts of resistance or complicity. I do not know what it means to fictionalize a war as it unfolds in real-time.

All I know is that the writing doesn’t help. The poker doesn’t help. The brain teasers don’t help. But they distract. And perhaps the project at the heart of Falling Man is to wrestle with whether this coping is constructive or only evasive. Because these rituals might be the self-soothing gesture of a finger in your mouth. Or else a gesture of two fingers, planted firmly in your ears.

It is nearly impossible to discuss Falling Man without discussing its most daring formal conceit, which involves extended passages from the perspective of the ringleader of 9/11, the very real Mohamad Atta. Especially considering that the novel was published a mere six years after the attacks, its ending is one of the most brazen pieces of American fiction I have ever read.

-JSR

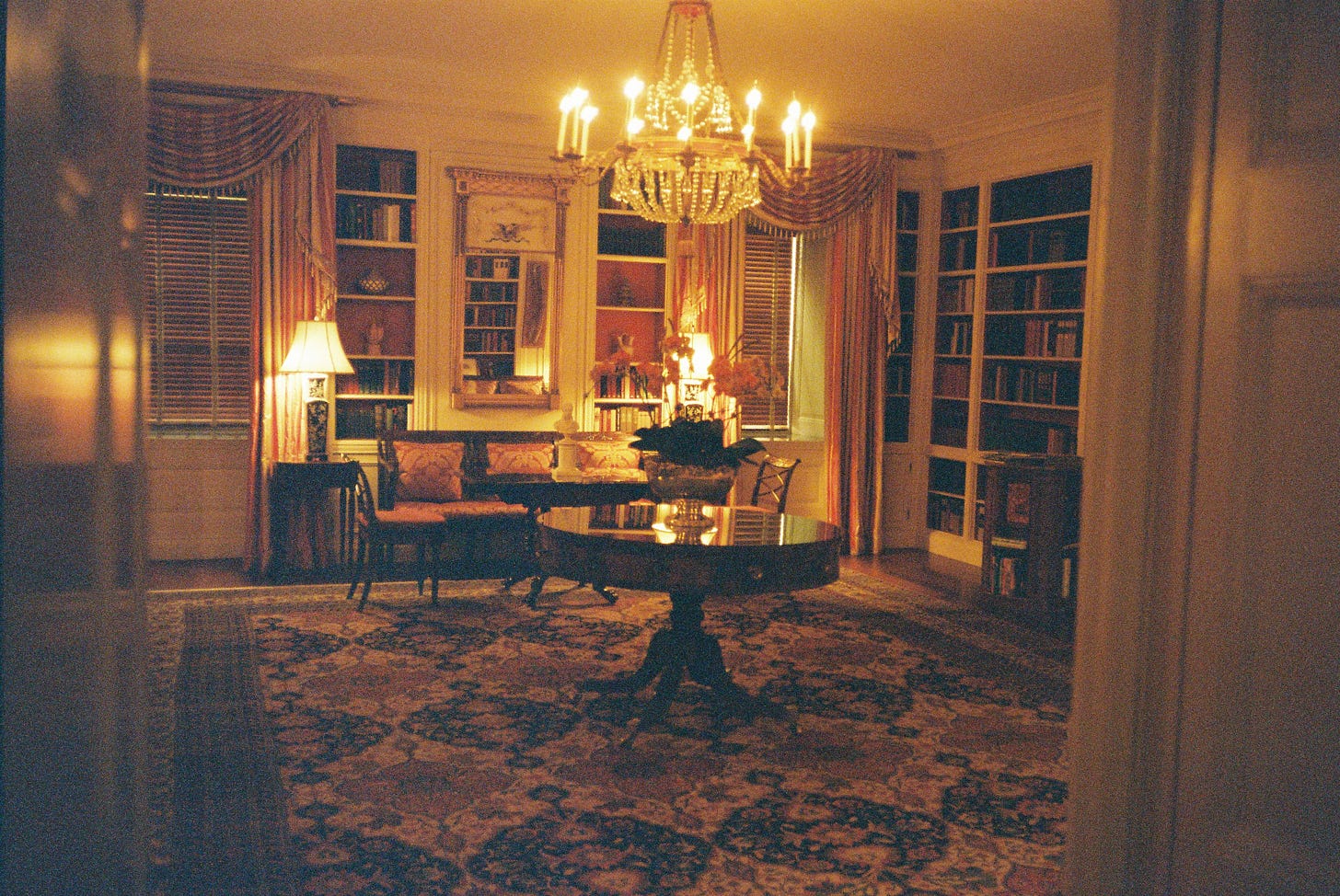

P.S. These photographs come from a family trip to Washington, D.C. this past May. And yes, that first photograph is a real photograph of a real portrait hanging in the actual White House. I know.